Of all the mythical monsters that people know, the Kraken is probably one of the most famous.

However, its fame has less to do with people studying ancient myths than it does with Liam Neeson’s oft-quoted “Release the Kraken” line in 2010’s Clash of the Titans.

The ironic part is that the Kraken wasn’t actually a monster in Greek mythology.

The Kraken is Norse mythology. Commonly depicted as a giant octopus or squid, the Kraken was specifically mentioned by name in an 1180 manuscript by Norwegian King Sverre and by the name Hafgufa in the Icelandic hero saga, Orvar-Oddr, dating back to the 13th century.

This article will dive more deeply into the origin and evolution of the Kraken myth. I will also discuss what the Kraken is, where it appears throughout ancient texts, and why people commonly associate it with Greek mythology.

Also, see What Is the Bifrost in Norse Mythology? to learn more.

What Kind of Creature Is the Kraken?

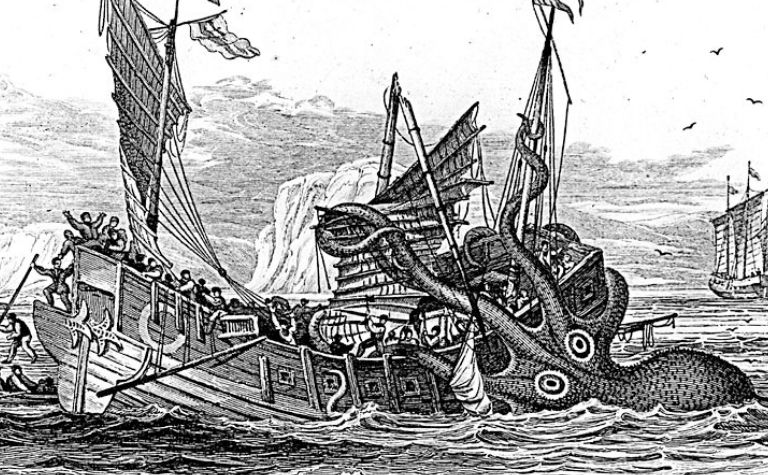

A Kraken is a creature portrayed as an unbelievably massive squid- or octopus-like sea monster.

However, that wasn’t always the case. For example, in Jacob Wallenberg’s book Min Son På Galejan (“My Son on the Galley”), Wallenberg refers to the Kraken as a “Crab-fish.”

Various other works of literature and pieces of art have also depicted the Kraken as a giant crab-like creature with pincers, legs, and shell-like armor.

However, the image of the giant squid/octopus Kraken is the one most people tend to believe.

The exact physical description varies from story to story and storyteller to storyteller, and the details, such as the number of tentacles it has and the color of its skin, often change.

There are, however, a few things that seem to remain constant throughout all versions of the stories, which are the Kraken is:

- It is a giant monster

- It has a huge, terrifying mouth

- Lives in the sea

- Comes out from the depths to destroy ships and eat unsuspecting sailors

But why did people “invent” the Kraken in the first place?

Also, see Are Norse Gods Good or Evil? to learn more.

What Is the Story of the Kraken in Norse Mythology?

The Kraken story is a popular part of Scandinavian folklore and is not found in actual Norse mythology tales.

The mythology was likely created by seafaring men – Vikings or traders – and passed first orally and then through written correspondence to their family, friends, and other seamen.

According to Henry Lee, author of the 1883 book Sea Monsters Unmasked and Sea Fables Explained, one of the earliest recorded mentions of the Kraken was by King Sverre of Norway, who claimed he saw the monster and that it was “colossal in size, as large as an island.”

King Sverre went on to say that the Kraken was only one of many ferocious sea monsters but claimed that it was more than capable of sinking ships.

He finished by saying that it “haunted the seas between Norway and Iceland and between Iceland and Greenland.”

Later, in the 13th-century heroic saga Saga of Örvar-Oddr, the author speaks of two other great sea monsters, Hafgufa and Lyngbakr.

Of the two, Hafgufa is described much like the Kraken, and when they told these tales later, storytellers often substituted the Kraken name for Hafgufa’s.

In Saga of Örvar-Oddr, the Kraken (Hafgufa) is described in the following way:

“Hafgufa is the largest monster in the sea. It is the nature of this creature to swallow men and ships, and even whales and everything else within reach. It stays submerged for days, then rears its head and nostrils above the surface and stays that way at least until the change of tide.”

As a result of stories like these, Scandinavians knew all about the legendary Kraken, and sailors and seamen were very superstitious about running into it on their travels.

Of course, the Kraken was only a myth, so they had nothing to fear…or did they?

Also, see Does Norse Mythology Have a Bible? to learn more.

Kraken: Myth or Reality

Luckily – or perhaps sadly – the Kraken is a myth.

However, scientists, archaeologists, and literary scholars alike believe that those early Scandinavian sailors really did see a giant sea creature that terrified them.

The Kraken was most likely the giant squid, Architeuthis dux, which can grow up to 46 ft (14 m) long and weigh over 600 lbs (272 kgs).

Scientists estimate that the largest of these creatures can reach lengths of 60 ft (18 m) and weigh up to 1,000 lbs (453 kgs). Even the 46 ft (14 m) ones have eyes as large as basketballs or human heads.

With that kind of information, it’s not hard to see how sailors living before the time of modern science could see something like that and think it was a giant sea monster.

What Is the Origin of the Kraken’s Association with Greek Mythology?

The Kraken’s origin was associated with Greek mythology starting in 1981 when Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released the original Clash of the Titans movie.

In it, the Kraken takes the place of the Greek sea monster Cetus Aethiopicus. The Kraken also appeared in the 2010 remake of the film.

Until the Kraken appeared in a Greek mythology-related film, no one associated it with the Greeks.

Giant sea monsters existed in Greek mythology.

Scylla and Charybdis are probably the two most popular, with Cetus Aethiopicus following closely behind them. However, none of them looked the way the Kraken is described.

Scylla looked more like a hydra, having six dinosaur-like long necks with six heads and rows of sharp teeth. She also had 12 feet and supposedly barked like a dog. Charybdis, on the other hand, was a whirlpool.

She was a sentient being, even called a goddess in some tales, but her physical form was a whirlpool.

Cetus Aethiopicus was perhaps the closest in the form to the Kraken. The stories sometimes described her as a sea serpent.

In other versions of the myths, she had a dog’s head and the body of a whale.

Sometimes, the myths simply referred to her as “a giant sea monster,” which is probably why the people involved with Clash of the Titans decided to turn her into the Kraken.

Final Thoughts

The fact remains that the only Kraken-Greek mythology associations that exist are those that Hollywood put into the world. The Kraken is 100% Norse/Scandinavian.

References:

[1] Source

[2] Source

[3] Source

[4] Source

[5] Source

[6] Source

[7] Source

[8] Source

[9] Source

[10] Source